Return to Harry Stephen Keeler Page

Chinaman’s Chance: The Life of Gordon Highsmith

By Fender Tucker

Nothing is known about Gordon Highsmith, the Sinologist who collected the aphorisms and sayings found in The Way Out, except what is revealed in six novels by Harry Stephen Keeler, all written in 1940 and published soon after. It’s as if the man had suddenly appeared on earth, produced a most remarkable book, then vanished as quickly as he had come.

For clues to this mystery, we’ll have to consult those six novels, and luckily, we have the very tool we need for this task: the Keeler Kanon. Thanks to the decision of Ramble House to reprint every novel Keeler ever wrote in scanned, OCRed text format, rather than facsimile copies of the books published in the 20s, 30s and 40s, the Keeler Kanon is a reality. All of his novels can be searched for keywords at giga-hertz speed by modern computing machines. The Keeler Kanon has been used extensively in writing this introduction.

The six novels (with the years they were written) are:

The Peacock Fan (1940)

The Vanishing Gold Truck (1940)

The Case of the Two Strange Ladies (1940)

The Book with the Orange Leaves (1940)

The Sharkskin Book (1940)

The Case of the 16 Beans (1943)

The first of these, The Peacock Fan, has the most extensive “history” of Gordon Highsmith and it’s contained in the following statements by Highsmith, as he sits in his death row cell, awaiting execution for the murder of his wife.

“I was born (in Dubuque) on July 20th, 30 years ago (1910)—that is, I’m 30 years and a fraction of a year old . . .

“My father was Alyster Highsmith, for many years secretary to the American Legation. So good a man he was, that he was kept on through many legation changes. My mother was Mary Highsmith. I went to China with my parents when I was 3 years of age. . .

“(I returned to America) five years ago—when both my parents were killed in a wreck on the Shanghai-Hangchow Railway. . .

“Both were born here in America. Father in Dallas, Texas—of American-born parents. Mother in Schenectady, New York—of American-born parents.”

The details of his crime are concisely described.

“The murder for which I’m to hang took place October 20th. A year and 2 days ago. The trial took place December 10th, approximately 10 months ago. I was convicted December 13th. My attorney—now dead—appealed on the 15th. The conviction was confirmed June 10th by the Court of Errors. It was then taken to the State Supreme Court. Which also confirmed it—and refused a new trial—both of those rulings on September 20th, a month and 2 days ago. My execution was set for October 22nd, and—well—that’s tonight. Day before yesterday the governor refused clemency. Of any sort. Pardon or commutation. And that’s the chronology of my case.”

While it would seem that a trial for one’s life for murder would be a defining point in one’s life, the trial and murder only tangentially figure in his publication of The Way Out, so it is left to the reader to read The Peacock Fan to find out more about the courtroom drama and disposition of the case.

More about Highsmith’s early education is touched upon in The Peacock Fan, including how he became a Sinologist and got interested in the “wisdom” of the oriental mind.

“I began practically when I was 3—with an old English-speaking Chinese tutor who was a descendant of the Kung family of China, of whom Confucius was the head. . .

“Confucius made none of the so-called wisecracks that authors sometimes attribute to him. Wisecrack being, in this case, I suppose, the typically terse, typically salient, bit of Chinese observation tempered, as the true Chinese wisdom always is, with humor. The sayings of Confucius, unlike many of the other Chinese philosophers, are not aphorisms, in the strict sense of the word. They are short—some of them—and they are medium lengthed—many of them—and some are long—and all were collected, after Kung-Fu-Tse’s death—as the ‘Confucian Analects’—by his disciples. . .

“(I) work(ed) on this book, off and on, in the Royal Chinese Library since I was a boy in my teens.”

Many other matters touching upon the copyright status of The Way Out (which Ramble House is essentially ignoring) are brought out in The Peacock Fan, and the book is highly recommended for anyone wishing to know more about publisher/author relations circa 1940.

Keeler also decided upon a format for utilizing the wisdom found in The Way Out in The Peacock Fan: a character would read a passage from The Way Out, use its oblique advice to plan a stratagem to win the day, then reveal the aphorism in the last chapter, explaining how it helped him. All five novels use this plot device. The aphorisms used in the novels are marked by footnotes in the text of the Ramble House edition of The Way Out.

When The Way Out was introduced, it was described as a “crimson-covered” book, about an inch an a half thick. As we will see, it changes a bit as time progresses.

We next encounter the book o’ wisdom in The Vanishing Gold Truck, a Screwball Circus novel laid in Idiot’s Valley USA, the unnamed state where Old Twistibus meanders between Foleysburg on the west and Pricetown on the east. Highsmith is not mentioned as the editor of the book, and the aphorism that helps truck driver Jim Craney across Old Twistibus is seemingly thrown in as an afterthought. Each of Keeler’s nine novels about the Screwball Circus world involve a truck that must traverse the windingest road in the country and apparently Keeler felt that at least one of them deserved a celestial solution.

The book, as described in The Vanishing Gold Truck, is a “bright scarlet book, without a jacket.”

Highsmith and The Way Out are next mentioned in The Case of the Two Strange Ladies, although the author does not make an appearance in person. TCOT Two Strange Ladies is very much a Phoenix Press book, involving the discovery of two beheaded female bodies, one white and one black, with the heads apparently transposed. Sounds like a situation ripe for oriental wisdom and Keelerian knowledge! This time the red-covered book is printed on green leaves and while there seems to be a distinct shortage of copies in existence, a bookseller, Mr. Solomon Silverspectacles of London England, is revealed to have a room full of them.

The Way Out soon makes it to titular status in The Book with the Orange Leaves. The cover is still red—although the book has been torn in two and a crude grey cover has been affixed to the latter half—but now the leaves are orange. Only one copy is purported to have been printed—or at least be in existence. A diagram, printed in green ink, plays a major part in unraveling the webwork mystery of The Book with the Orange Leaves, and is reproduced in this edition of The Way Out.

Highsmith is mentioned, but only as the author of The Way Out and doesn’t make a personal appearance.

By the time the book is used as a title for Keeler’s next novel, The Sharkskin Book, it has donned a “queer flexible ragged-edged bluish-gray leather binding. Sharkskin!” The color of the leaves is not mentioned. But, as always, the wisdom gleaned from the collection of aphorisms is used by an unfortunate innocent person to protect himself from the long and wrong arm of the law. The subtitle of The Sharkskin Book, By Third Degree, gives you the theme of this fascinating book, which is how a person can protect himself from the cruel sadism of our legal system and its brutish minions, the cops. If you are allowed by the powers-that-be of your country to read only one Keeler novel, make it The Sharkskin Book. You’ll thank Harry as you’re led into the dark back rooms of the police station to be “questioned”.

We finally come to the last Keeler novel which features Highsmith’s wonderful collection of wisdom, The Case of the 16 Beans. It’s another wacky Phoenix Press book and was written and published three years after the others were penned. The cover of The Way Out has reverted to bright red and it’s essential to the goals of a young man caught up in a ridiculous controversy over a will.

In this swan song, Keeler decided to grace us with more history of Highsmith and his wondrous book, almost rubbing our noses in the book’s scarcity and value.

“Well, the work in question was created by a chap named Gordon Highsmith. Brought up in China. And was published in both England and America, though by two different sets of publishers, quite naturally. The British edition, however, is as non est as is the American. Yes, the great blitz in the British publishing district, during the late war. Only two copies of that edition are known—so-called author check-copies—printed, as such are, on green paper—and both today in the hands of known collectors. As for the American edition, of which we’re now speaking, the work was issued by a firm in Philadelphia known as the Vinnedge Brothers. The Vinnedge Brothers are out of the publishing business, and, so far as anybody seems to know, dead. Which may be just as well, since one of the brothers had a weird flair for—but—er—I won’t go into that! The author of the work, however—yes, Highsmith—has not been heard of for some years; he is presumed to have died in the North African Tunisian campaign, from a bursting German shell. So o o the book, you’ll understand, can’t be reproduced—at least certainly not in American edition, anyway—since the author, missing, owns the copyright, and the Vinnedge Brothers firm, dissolved and all, owned the American publication rights. And—but is this clear?”

Again we find that Keeler had knowledge of the labyrinthine copyright status of The Way Out. It makes one wonder why he did not champion its republication for modern readers, as Ramble House has. Perhaps he was too close to the subject? Perhaps he had too intimate a relationship with publishers who were stingy with royalties and payments? Maybe he felt that such a book was too powerful for modern readers, and that such knowledge should be accessible only to those who had the gumption to search out the last remaining copies?

Now that you have the book itself in your hands, you be the judge. However, if you are interested in researching the The Way Out story, be sure to read further into The Case of the 16 Beans. It’s filled with legal and copyright information about it.

Perhaps you have noticed that this essay subtitled “The Life of Gordon Highsmith” contains precious little about the actual life of the author, and has instead fugued into a history of The Way Out, as described in the works of Harry Stephen Keeler? This is because the only evidence of Gordon Highsmith ever existing is in the six Keeler novels and the few existing copies of The Way Out that may or may not be floating around.

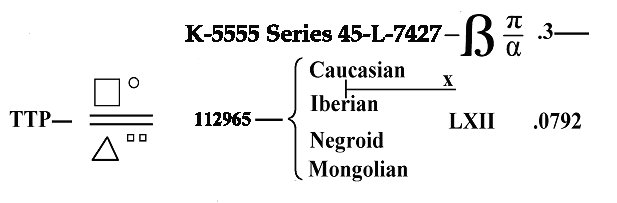

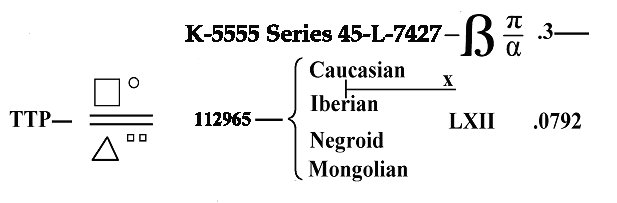

Why is Harry Stephen Keeler the only connection to this enigmatic Sinologist? Perhaps the clue to this mystery is found in two other Keeler novels, The White Circle (1954) and Strange Journey (1965). In these two novels, which HSK called “skience friction”, he tells of a visit to Scientifico Greenlimb, a Washingtonian scientist who lived at a roominghouse called “Ramble House”, by a man from the far future. The time traveler, whose name was

but is called for convenience, K-5555, never mentions Gordon Highsmith or The Way Out, but doesn’t a person who flits in and out of history suggest a potential time-traveller? And what better way to influence the lives of people in the ancient past than to supply them with a book of “wisdom” purportedly collected from the all-time inscrutibles of antiquity, the Chinese?

Until a new form of research is invented, something like the world-wide web but without out all of its inaccuracies, the question of the provenance of Gordon Highsmith will have to languish in uncertainty.

It’s a languishing that I think Harry Stephen Keeler would have enjoyed. Don’t you?